Towards net zero – A collective effort

June 2021

By James Purkiss

The climate and biodiversity crises are dual global emergencies that demand personal reflection alongside collective action. Last month I posted a short piece to announce our decision to sign up to the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge. This collective initiative, led by the Royal Institute of British Architects, aims to help the construction industry achieve net zero carbon for the whole UK building stock by 2050. Requiring signatories to share information on the energy performance of their projects, the initiative recognises the value of sharing our individual experience for wider sector progress.

In this, and subsequent blogs, I will share some thoughts on the particular challenges and opportunities that we have experienced at Archio in working towards net zero.

Could the switch to low emission heating expose residents to fuel poverty?

This is a challenge faced by many of our clients. Social housing providers must factor residents’ fuel costs alongside emissions when deciding on the best heating strategy.

The increasing decarbonisation of the electricity grid means that electric heating, usually delivered via air source heat pumps, is now the preferred option on almost all of our projects. As well as reducing emissions, omitting gas from buildings also removes safety and maintenance issues. However, electricity currently remains more expensive than gas per unit of energy, meaning residents could be exposed to unaffordable fuel bills if we do not minimise the amount of energyrequiredthey needto heat their homes.

So, to avoid unaffordable fuel bills we must deliver buildings that are more energy efficient. A challenge for us, and for the whole construction industry, is that new buildings regularly fail to achieve their expected energy performance. According to data collected by CarbonBuzz, a joint RIBA and CIBSE platform, new buildings, on average, consume between 1.5 and 2.5 times more energy than expected.

How can we help to close this ‘performance gap’?

The performance gap can result from inefficiencies in the construction and the operation of a building. As architects, we can help to close the performance gap by designing buildings that are easy to construct and subsequently operate. One way that we can do this is by adopting Passivhaus design principles and by targeting Passivhaus certification. Passivhaus buildings are certified through an exacting quality assurance process by the Passivhaus Institute in Germany. By limiting heat losses, through airflow and through the building fabric, Passivhaus buildings use less than 15kwh of energy per m2/year. For comparison, the space heating demand of the average UK home is currently about 145 kWhm2/year and a new build home about 50 kWhm2/year.

Determined to tackle fuel poverty and reduce emissions, Camden Council adopted this approach for the largest UK residential Passivhaus project to date, for almost 500 homes on the Agar Estate. Camden chose Passivhaus for this project, the first phase of which completed in 2018, because they could see that the higher build quality and reduced maintenance costs over the lifetime of the buildings would offset the initial increased capital cost.

Post-occupancy monitoring of the first phase of the Agar Grove project suggests that the Passivhaus approach has delivered a 71% reduction in heating bills compared to 2018 Annual Fuel Poverty statistics. It is therefore understandable why other social housing providers and local authorities, including Ealing, where Archio’s director Kyle is a member of the Design Review Panel, are now adopting the Passivhaus approach.

We are excited to be working on a number of projects targeting Passivhaus certification, but remain aware that design buildings that are easy and intuitive to operate will be crucial to achieve, or even better, the heating bill reductions seen at Agar Grove.

The Archio approach

As Kyle described in a previous post, we always try to put ourselves in the shoes of future residents. This includes asking ourselves if it will be clear to them how to operate their home most efficiently, as turning off the wrong switch in a Passivhaus home could end up increasing the heating bill. On the Agar Grove project, user guides on how to operate the homes were produced for residentsOne approach is toprovideresidents with bespokeuser guides, but what will happen if theatguidesareislost or forgotten? How will a future resident know how to operate their new home efficiently without learning from the previous occupantif that guide is lost?

We must also account for the reality that different residents will have very different demands of their homes; no two homes and no two households are ever the same. As architects, we must always consider the role, impact and experience of the individual user in the ultimate success of the project as a whole. In much the same way, the RIBA 2030 Climate Challenge will rely on individual action for collective progress towards net zero.

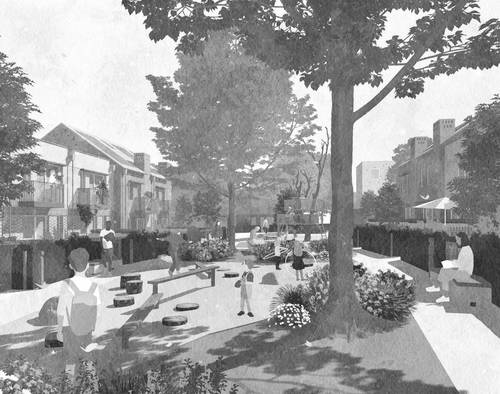

Our project at Becontree Avenue will be electrically heated using air-source heat pumps