Maiden Lane Estate Visit

January 2018

By Robin Farmer

I approached the Maiden Lane estate from the south. The Estate stands in stark contrast to (and thanks to the east-west Overground line) is cut off from, the booming 67-acre Kings Cross redevelopment, centred around Granary Square.

Walking around this low-rise, high density housing, it felt very easy to forget that multinational media-tech behemoths such as Google and YouTube, and institutions including University of the Arts London, are setting up shop just a short walk away.

With its neighbouring development big on big buildings, big ambition and big public spaces, this pocket of London, with its intimate streets and back-alleys, felt, somewhat perversely, like a breath of fresh air. I found the ideas at play at Maiden Lane as big, bold and ambitious as anything built or planned Kings Cross.

Maiden Lane was developed in two phases: Phase I (1976-81) was designed and delivered by Gordon Benson and Alan Forsyth of the Camden Architects’ Department, and Phase II delivered by others at the Department. The development, which mixes terraced houses, maisonettes, and flats, is characterised by the sculptural Corbusian qualities of the white, painted concrete volumes with deep, gridded facades.

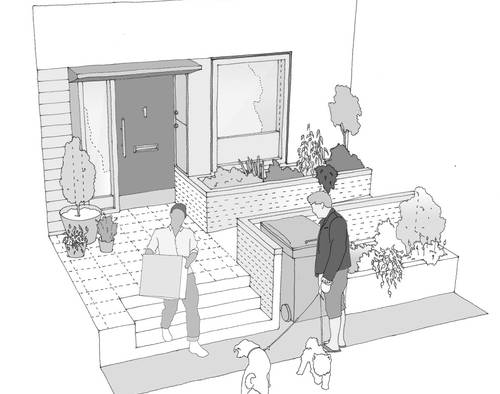

These concrete volumes engage with a red brick landscape punctuated by planters, which negotiates the natural fall in landscape from east to west. This topography is exploited in section to provide level-entry access at the upper floor to some of the terraced houses, which have covered points of entry which incorporate bin stores, whereby the garden gates to the lower floor leads onto the pathway access to the next terrace, and so on, down the hill.

I was aware, walking around the estate, of a contentious and contested history of occupation. Despite some initial critical success, the Estate soon fell victim to crime and vandalism. Critics of the estate levied accusations that Maiden Lane felt ‘cut-off’ from the surrounding area, and had become a surveillance black-spot. Reports of police officers unwilling to visit the estate (alongside pizza delivery drivers worried about their bikes being nicked) reinforced a stigma that this had become a concrete jungle, a late Modernist ‘Wild West’ of aggregate and cement.

Despite these criticisms, I found much to like at Maiden Lane. It seems evident that the Estate is in a much better place today, with renewed work and energy being invested in new landscaping and housing following the appointment of PRP to add 265 new homes to the site.

Typical to Benson and Forsyth’s work, I found the sectional relationships consistently surprising and engaging, particularly in the earlier terraced houses. Where large-scale modern housing projects in the capital seem to desperately rely on replicated plan layouts stacked one on top of the other in endless repetition, the example of Maiden Lane stands as a vital reminder that architects design well in three dimensions.

It might be argued that Benson and Forsyth applied the deep-section approach somewhat more convincingly elsewhere – Branch Hill for example – but in any case, this approach to design and delivering light, bright domestic interiors with a sense of surprise and volumetric rigour felt like a diamond in the rough.

There are great cues for architects here; the carpet of low-rise, dual-aspect accommodation sets a scene that feels socially enlivened; a lineage that can be traced to modern-day practice through the likes of Peter Barber. In a cultural landscape where development increasingly seems to tend to the risk-averse, the brazen ambition on display here should be celebrated. I left the Estate totally energised.

_slides.jpg)

_slides.jpg)

_slides.jpg)