Early Doors – An Abridged History of the Public House

April 2016

The story of the British pub is as old as Britain itself. A cherished national institution, a good pub is at once familiar and traditional but delightfully idiosyncratic and unique so that our personal favourite, our very own ‘local’ is quite unlike any other, in our eyes at least.

A ‘secular church’, the pub binds together communities, forges and preserves friendships and breaks down social inhibitions. Pubs strike a delicate balance between the comfort of a front room and far enough away from our own front room to feel out and in public. From its very beginnings, the pub’s story is one of evolution and reinvention, reflecting cultural and societal shifts across many eras. The pub has continually adapted to change to remain an integral and enduring part of British culture.

WHAT’S YOUR POISON?

The pub’s history on the British Isles began almost 2000 years ago when invading Roman forces set up tabernae alongside newly constructed roads to refresh their troops with wine. As the climate of the British Isles was too cold for their grape vines, the taverns (as they soon became known) began to serve the local beverage: ale. Thus, taverns were also known as alehouses.

In the centuries that followed, the taverns, inns (which also offered food and accommodation) and alehouses adapted to serve the tastes of the many tribes and mercenaries who invaded the isles. The Vikings brought mead, a drink made from honey whilst the Saxons liked ale, though they called it ‘beor’. The Angles and Jutes each brought with them their own strengths and flavoured versions of the barley-based drink. During this time beer was often safer to drink than the local water!

SIGNS OF THE TIMES

The Roman tabernae promoted their trade by hanging vines above the front door. This visual marker evolved into a painted pictorial sign identifying the building as a pub, often with no written words for a largely illiterate society. Making reference to the stuff of alcohol production (hops, barley) and storage (tuns, barrels) the hinged sign has also represented a wide range of things.

Built in 1189, Ye Olde Trip to Jerusalem in Nottingham claims to be the oldest inn in Britain and its name and simple sword motif painted on the wall marks its role serving knights who were on their way to fight in the crusades.

Famous battles, fairs and festivals and quotes from literature also produced some of the country’s most recognized pub names. Religious figures, monarchs or famous military leaders were soon joined by earls, landowners and successful sportsmen of their time in having their names and likenesses immortalised on the swinging signs.

The royal crest or ‘arms’ of the many kings and queens were displayed to show loyalty to the monarch. Pub names also reflected the prominent building trades of the area. Masons, bricklayers, builders, carpenters, blacksmiths and plumbers also displayed the ‘arms’ or crests of their trade’s appropriate London livery company. Often, a pub’s name hinted to the host’s secondary or previous profession.

A NAME ABOVE THE DOOR

By the 19th century, the term ‘public house’ was beginning to be used for a range of establishments which served alcohol: inns, taverns and alehouses. It was also around this time that the sale of alcohol began to be regulated and all pubs required a license to operate.

In the early 1800s, beer drinking was encouraged and seen as a safer and more socially acceptable alternative to gin, the potent spirit blamed for many of the social ills and lawlessness of the previous century. Whilst the ‘Gin Act’ of 1750 limited and regulated the sale of gin (the ‘vice of intoxication’), the introduction of a later law, the Beerhouse Act of 1830 actually led to a ‘boom’ in drinking establishments.

With the enactment of the new law, anyone with a license could brew and sell beer. 30,000 new ‘beerhouses’ opened with ‘tap rooms’ set up in people’s own homes and shopkeepers began to sell beer alongside their usual wares and merchandise. These laws were the precursor to today’s Licensing Act which still permits the sale of alcohol and late night refreshment and entertainment.

REFLECTED IN THE CEILING

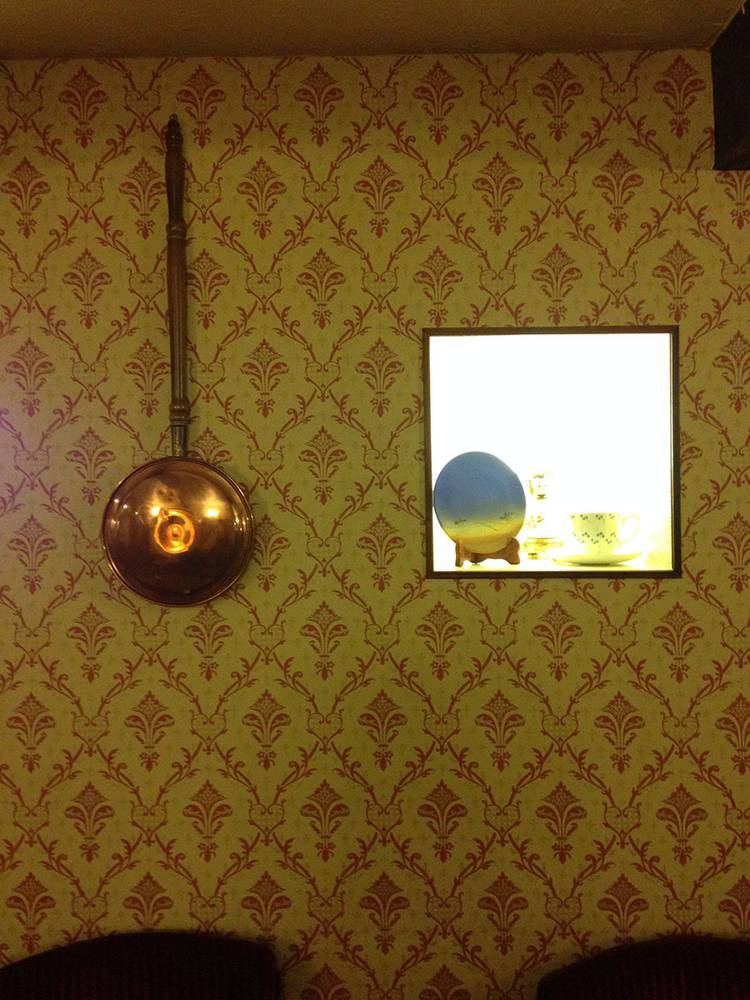

The 19th century is widely accepted as the ‘golden age’ of city pub architecture (in London especially) and produced many notable interiors with elaborate tiling, etched glasswork, decorated mirrors and carved wood and timber paneling. Pubs of this period often had separate rooms and areas to accommodate a range of activities serving different strata of clientele and highlighting divisions between class and social position.

Saloons and lounge bars were introduced as upmarket alternatives to the ‘spit and sawdust’ public bar. With softer seating, carpeted floors and entertainment on offer, an entrance fee or higher drinks prices ensured only the wealthy frequented these parts of the pub. Snug bars were made even more separate from the main areas, affording extra privacy for their patrons. This was a chance for women, whose presence in pubs was not socially acceptable to also enjoy a drink, with frosted glass screens maintaining a level of discretion. On-duty policemen were also known to make use of this opportunity for a ‘discrete’ drink. ‘Snob screens’, as they were known (etched glass in a hinged frame) allowed drinkers of higher classes to observe working class drinkers without being seen and as an aid to prevent being overheard by a snooping bartender.

Today, in a society where such class divisions are less apparent, many of these separate rooms have been brought together to form largely open plan pubs. The remnants of these old rooms and partitions can often be read through the structural beams which run across the ceiling.

NEXT ROUND

The pub’s next chapter of its history is currently being written. Some are under threat of closure and are struggling with a new set of challenges. Just as the pub has done since its inauguration on these shores almost 2000 ago, so it must adapt once again if it is to remain a part of our communities.

FURTHER READING

http://www.ucl.ac.uk/~ucfbrxs/Homepage/walks/PubGeology.pdf 19th century London city pubs

.jpg-web_slides.jpg)