Wifi Networks as 'Digital Territories'

December 2015

Wi-Fi, the wireless local area networks found in many homes and most businesses across the country are inherently spatial. They can be thought of as a sphere of accessibility radiating from either a single, central ‘hub’ or from nodes or points that enable a connection to the network and the Internet. Proximity is essential to ‘join’ with and utilize these zones of connectivity, and occupying them with a suitable device often negates the need for an actual physical data connection. Walking around the city, we pass through hundreds of these territories; multiple overlapping radii of Internet ‘hotspots’.

What's in a Name?

Physically invisible and transient they are nonetheless a form of territory. Network names appear and disappear on the screens of smartphones and other devices as they come into and drop out of range. When looking for a suitable local connection, they have the power to alter our behaviours. Imperceptible ‘agents of behavioral change’, we are often drawn to places offering open, free, stable and good quality connectivity.

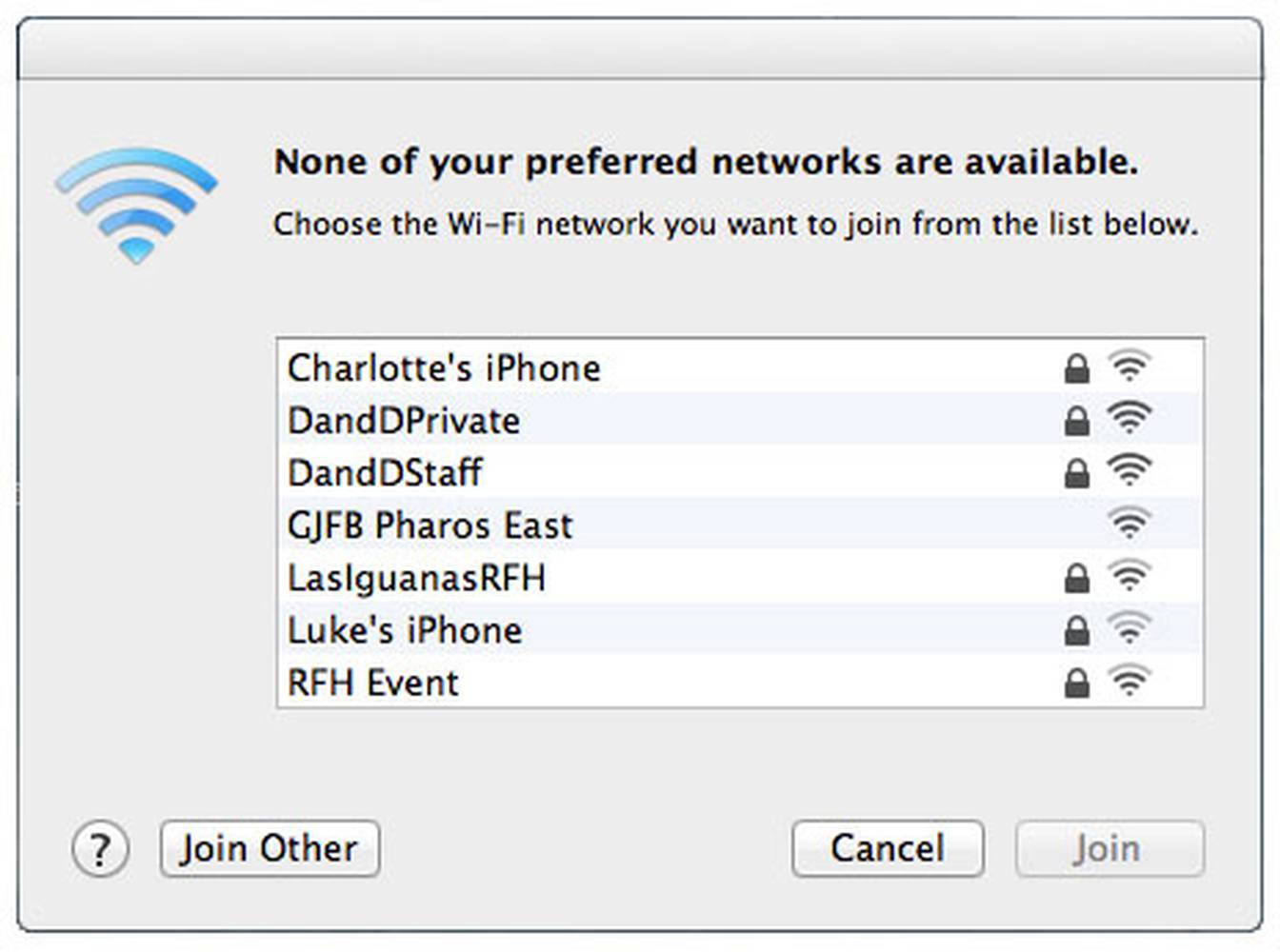

The process of connecting to any network displays all other potential connections within the vicinity. Dropping down the list of ‘available networks’ offers a dynamic billboard of open Cloud networks, cafes and bars soliciting their ‘free Wi-Fi’ and alongside private and secure home hubs and other devices with bespoke monikers.

To locate and reconnect with familiar and trusted or ‘preferred’ Internet connections, Wi-Fi hubs are identified by a string of 32 alphanumeric characters known as the SSID (Service Set Identifier). Often simplistic (Router), generic (BTWifi-123) or a seemingly random code (bcf2af976f28), these names can also be modified and personalised. They often hint at, or are in parity with the place at which they originate; a place (TheLordClydeWifi), person (Nicks Hub), business or building name. However, as they are editable, these network names can be made into personalisedbroadcaststhat are mostly benign and/or obscure but can also be deliberate and targeted.

These short messages can be used to express themselves, communicate with one another, vent frustrations, declare affection (NeedingAConnection), make political statements (VoteForPedro) or simply used to say hi (HelloWorld) . In built up areas, they could be directed towards neighbours (KeepTheMusicDown, StopWearingHeels), or warnings to hackers and opportunists attempting to gain access to their networks (StayOffOurNetwork). Wordplays, puns and light humour can also feature (PrettyFlyForAWiFi, The Promised LANor other examples) simply to crack a joke.

Cyber Graffiti

David Meerman Scott, a marketing strategist, saw the subtle marketing potential in renaming Wi-Fi networks, branding it ‘cyber graffiti’, with the network name utilised as a form of publicity and powerful promotional tool. Despite the limitations on the length of the message, the potential audience is huge. Meerman writes:

“Imagine how many people are seeing that network name. If it's in a crowded city, it could be thousands a day.”

Rather than ‘spamming’ or forcefully directing information toward people (like a poster, billboard or graffiti tag), these communications reach only those who are currently on the lookout for a network. Somewhere between ‘interruption marketing’ and ‘permission marketing’, attention is drawn away from the task in hand but you have to be within reach and viewing the available networks for the message to get through.

‘Cyber graffiti’ and the spray painted ‘tags’ of its physical world namesake have more than a few similarities, none less than the objective to be seen or read. Both digital and physical media share the appeal of ‘public notoriety of a name appearing all over the city’ and the satisfaction in displaying a message, conceivably seen by as large an audience as possible. Like spray-painted tags, these short digital transmissions are, as self-proclaimed Wi-Fi detective Alexandra Janelli describes an “easily changeable medium“. More dynamic than a sprayed tag scrubbed off or painted over the following day, these digital messages are less permanent and less visible.

During NYC’s worst spate of urban graffiti in the late 1970s, The New York Times described acts of graffiti as ‘cowardly vandalism’, but spraying in the city came with certain degrees of danger. With cyber graffiti, there is no longer a risk of being caught in a prohibited act, and gone is the physical danger of scaling the most visible points in the city like a road bridge of building overlooking a busy train line to daub a slogan. These fleeting broadcasts can be made from the comfort of the home with relative safety and anonymity.

The Physical / Digital Colission

Like a shortened tweet, thisdigital soapboxallows network administrators to broadcast whatever they feel, within the 32-character limit. However, the purely digital and global realm of Twitter is not contained or restricted by physical barriers. These Wi-Fi messages are limited to the transmittable range of the Wi-Fi hub and can be blocked and weakened by the physical world around them. Walls, books fish tanks and other networks interfere with and confine the extents to which they can be reached and read.

An unregulated form of expression, the renamed networks also have the ability to irritate and annoy. Uninvited, they appear to ‘write’ their short slogans on the screens of our digital devices as we look to find and reconnect with our preferred networks. As graffiti is often utlised as a territorial claim, so cyber graffiti invades the monitors of our computers and screens of laptops and smartphones which we deem as our ‘personal’ space, infiltrating that which we own, possess and attempt to control. It has the potential to ‘tag’ within our homes, making a ‘claim’ on the physical surface through which we view the digital world.

Further Reading

"The Tao of Wifi" New Yorker article by Lauren Collins