The Cul-De-Sac: Desirable Enclave Or A Dead End?

December 2015

Cul-de-sacs divide opinion between those who celebrate and yearn for the seclusion they offer, and others who criticise their disconnected form and the creation of convoluted and isolated settlements. One survey conducted in 2013 found that 88% of people considered this settlement type as their ideal place to live; a place “where your neighbours know your name” and the residents are amongst the happiest in the country. Other surveys show that homebuyers are prepared to pay up to 20% to secure a property on one, both in Britain and the USA. There are, however, elements to cul-de-sacs which deflate this idyllic picture and give weight to more negative perceptions from which the street type also suffers.

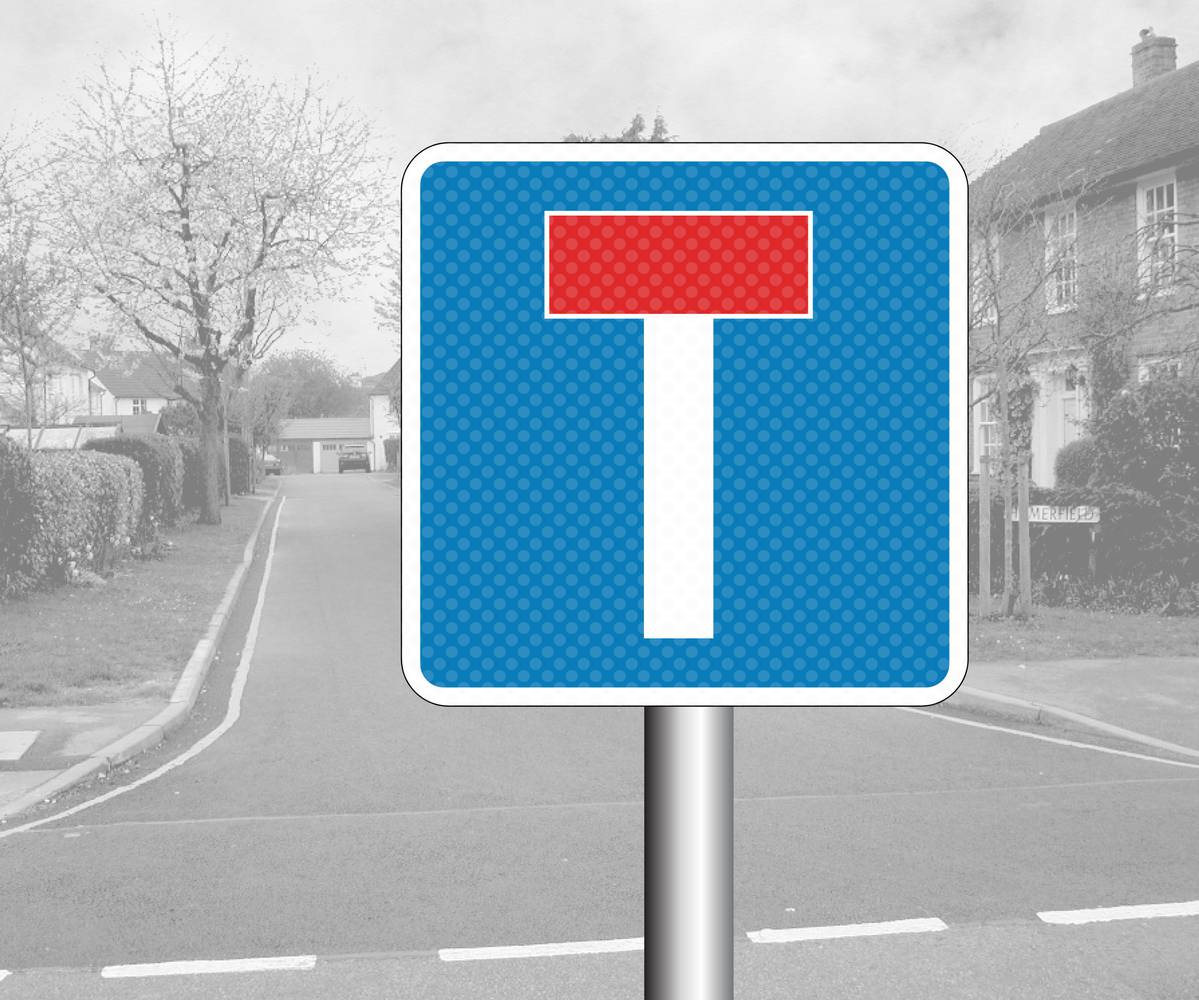

ONE WAY IN, ONE WAY OUT

The building of cul-de-sacs was banned in the UK until the 1906 Hampstead Garden Suburb Act legislated their use, defining them as “a non-through road with a maximum length of 500 feet/150m”. The origin of the phrase is French, meaning “bottom of the sac”, anatomically referencing a part of the body, shall we say, which deals with waste. It is not surprising perhaps that the French make no use of this phrase in their language to describe such a road, they prefer “impasse”. Cul-de-sacs also go by other aliases which are used in other contexts with negative connotations: no exit, dead end, no-through-road, blind alley. Open and connected at one end only, they lead nowhere.

Historically, dead-end streets were utilised by the ancient Egyptians, Greeks and Romans as a tactical defensive tool in the event a city came under siege. Attacking forces would struggle to understand and navigate the maze-like labyrinthine arrangements and could dangerously find themselves trapped in a street with only one way in and out. In today’s cities, these characteristics still confuse and disorientate, though these problems are faced by delivery companies and emergency services rather than the military.

DEFENSIBLE SPACE

In the 1970s, American architect and urbanist Oscar Newman suggested that residents of densely populated inner-city areas found it difficult to take control or responsibility for where they lived. With high concentrations of dwellings mixed in with shops, amenities and businesses, the city is a domain shared by residents, visitors, workers and tourists alike. This creates ambiguity as neighbours (too many that they’d all “know your name”) are indistinguishable from strangers making it, Newman argues, hard to protect your home, your ‘sacred space’.

As a response, he conceived the ‘Defensible Space Theory’ in 1972. The antithesis of the high density inner city, the suburban cul-de-sac shares much with Newman’s set of five principles which comprise the theory and propose how to reduce crime and design safer neighbourhoods. Cul-de-sacs belong to low-density areas, where clearly defined and identifiable territories manifest through garden fences and hedges with plenty of breathing space between the houses. These clear boundaries create a notion of territoriality, the first of Newman’s key principles; easily ‘defendable’ plots which reinforce an idea that one’s home is one’s castle.

“SAFER AND QUIETER”

By designing out shops and businesses, suburban areas comprised of cul-de-sacs become homogenous and purely residential. The disconnected nature of the single-ended street means that these places are not ‘destinations’, not for anyone but the residents themselves and their occasional guests. Single streets become whole neighbourhoods; insular, semi-private and shared only by those who live in, or are invited in to these areas.

The residents of cul-de-sacs become “key agents” in maintaining the security of their individual and collective domain. The street itself becomes part of thedefensible spaceincluded in the ‘home territory’ and aligns with another of Newman’s principles, that of enabling natural surveillance. The single entrance/exit means there is only one means of escape, acting as a passive crime deterrent so that the whole street can be surveyed from inside the home. Houses are adequately spaced and radially arranged around bulb-shaped road (modeled around a car turning circle), so as to keep watchful eyes on anyone entering the dead end street.

However, passers-by or newcomers are treated with suspicion as they are assumed to have no reason to be in an area with no ‘destination’. With no shops or businesses encouraging visitors, they have no ‘right’ to be there. An exclusive enclave is created, one which is designed to be strongly protected.

Another consequence of the lack of ‘destination’ is the perceived reduction of vehicular movement, with traffic calming being one of the cul-de-sac’s raison d'être. With no through-routes, only residential traffic should be present on these streets. By diverting any cross-town traffic away, the environment should be healthier and safer for the residents, especially for children who are able play out on the car-free roads. However, this does often mean that the traffic diverted from the cul-de-sac is merely rerouted elsewhere, not eliminated and, as there are no shops in the typical cul-de-sac, journeys for essentials are made longer and more often require the use of a car.

ROUND THE HOUSES

The interconnected city grid offers many different ways and alternative routes to reach a particular destination. Cul-de-sacs are harder to reach and deeper within the urban fabric. The cumulative effect of many one-ended streets across a suburb means the creation of a incomprehensible tangle of roads where there is often only one route option between most destinations. US-based designer, inventor and blogger Chris Nortstrom has identified some ridiculous detours and elongated car journeys across suburban America caused by the cul-de-sac’s often convoluted layout. Short walking distances are turned into huge circumnavigations of a suburban maze and he highlights the inefficiency these layouts create and the wastefulness and pollution in needless car travel.

This ‘problem’ as he illustrates, is resolved by adding a few small sections of road - relatively simple ‘fixes’. These however, transform these dead ends into through roads, something he discovers the residents of these cul-de-sacs are no too keen on as he canvasses their opinion on the proposed changes. Once these desirable enclaves are created, they are protected by residents, to the detriment of an efficient functioning city.

Being 40 years old, Newman’s theory is seemingly outdated. Well-designed places today should be legible where visitors can easily read the space and find their way around on their first visit, feel welcome and that they have a right to be there. Cul-de-sacs represent many of these older ideals, but they can, like Norstrom suggests, be modified and improved. Germany, and a number of other European countries adopt a type of cul-de-sac which isn’t totally closed at the end. The ‘living-end’ road configuration is closed to vehicular traffic but open to pedestrians and cyclists, promoting cleaner, more sustainable and healthier ways of moving around the city. Existing cul-de-sacs could be converted using this model allowing for a more interconnected urban framework and helping to eliminating car-dependent communities.

FURTHER READING

Defensible Space by Oscar Newman